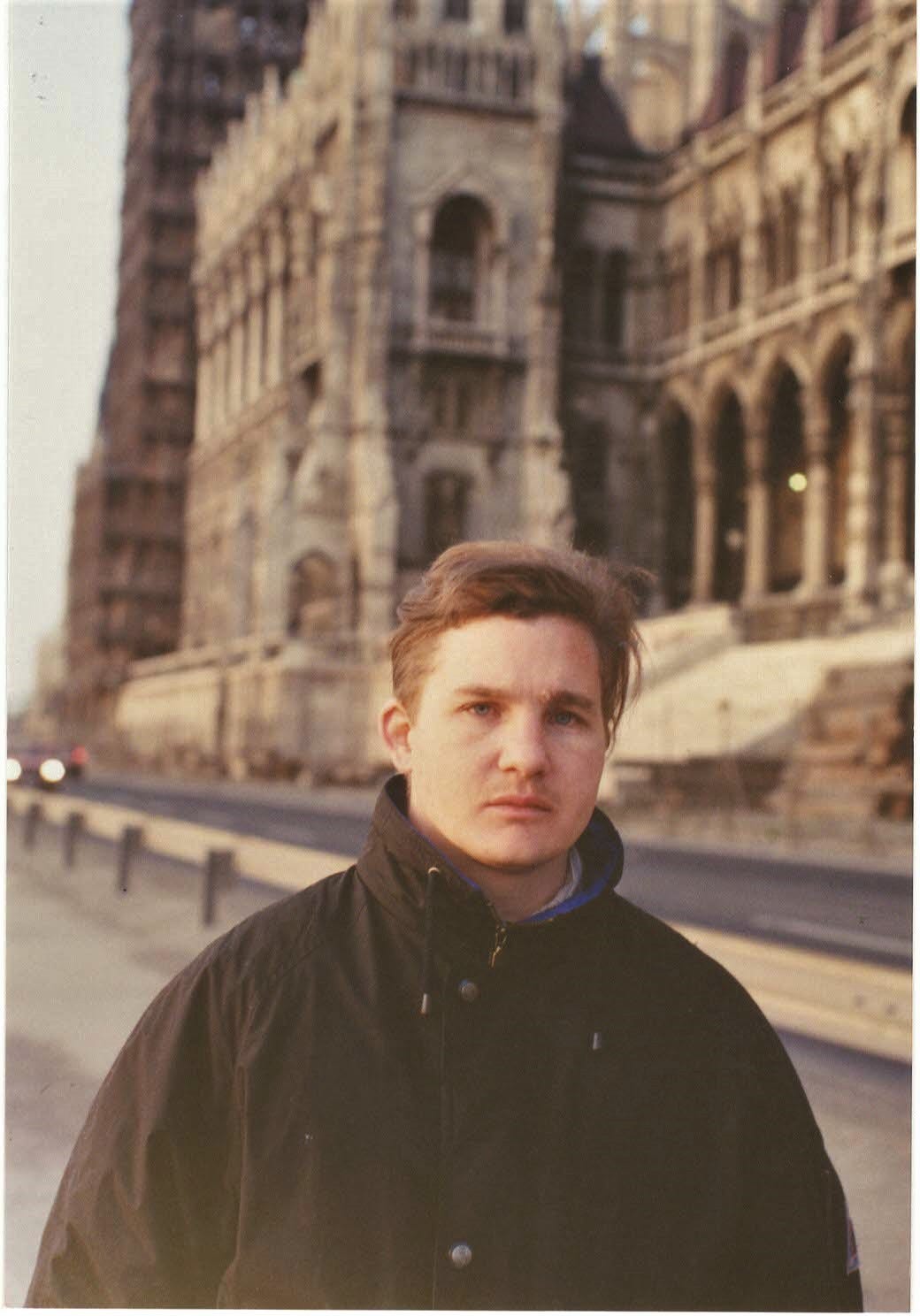

I was deep diving not long ago among actual physical photos for an old shot to be scanned and included in the print edition of a magazine interview with me about my old days in Budapest and I wanted to offer it up. Perhaps showing a life lived. The desperation of desolation. Maybe even a cautionary tale.

And the deep, slumbering wells of memory re-populated the active cells of the brain.

I am in front of the Hungarian Parliament in 1993-4, when the winter froze to the bone. We were sixthousandmiles from home and no way back for Christmas. We were broke.

There was a rustic tavern on the southeast side of Castle Hill near the bank of the Danube where you could drop in from the arctic during Christmas shopping for some fried pork and cold beer. It was almost hewn into the hill, as I recall. On the outer edge beyond the tourist zone. There were no Americans there. On the poor side. The smoke in the windowless establishment was Cancer itself rubbing his hands together in anticipation of the coming bounty, but the warmth was a rescue from the deep cold.

Unlike the tidy European and American tourists on the Castle Hill, these were working class Hungarians who liked to drink and liked to smoke. I felt at home among them and I spoke to them in their language (with a strange Miskolc accent - which is another story) as I ordered a soup and a dish of fried pork and deep, dark Hungarian beer, Dreher Bak. It is likely that I began with a large Hungarian szilva palinka - plum brandy - as it was normally the first thing a sensible person turned to when partially frozen. But it well could have been an herbal liquor like Unicum, which softened the mind as it brought one steadily back from the grip of the snow devil. The lusty plates of fried pork arrived as I dabbed it all with bread that moved in a basket from table to table, acquiring, among other things, cigarette ashes as it passed from customer to customer. Most Americans would not accept this. It did not bother me at all.

____

On Vörösmarty tér in the old part of Budapest there was always the Karácsonyi Vásár - the Christmas market. As we anticipated our yearly trip "home" to US, we also punctuated our shopping with stops for forralt bor - hot spiced wine - to keep warm in a world where the ice air crystalized the night. The cold was shocking, breaking through all manner of preparation. Hot red wine, sweetened and steeped in cinnamon and cloves, was available for a dollar a pour. It was an infusion of Christmas, deep into the soul as it burned from the inside. The warmth was anticipation of the arrival of our Lord Jesus Christ. Dicsőség az Istennek. Glory to God.

Our gifts to family in California in those days were brown homespun beeswax candles and tinned pork liver pate. I don't think, in retrospect, they were very well-received.

____

Under the outdoor marketplace, in the wine cellar under Kolosy tér in the third district of Budapest, a stone's throw from our flat on the Danube on Árpád Fejedelem útja - the very bank of the river - I was working on my diary, intended to be a book, while I was also working on long glasses of red wine, 30cl each. Hordói bor (look it up). It was somewhat dank without oxygen and I just kept filling up those empty lined diary books I purchased from the Hungarian stationary stores.

She was off working all day for the Western taskmasters while I worked on paper, reading, writing, and drinking the barrels dry. In my corner with my 30cl. My secret world.

A group of early afternoon drinkers arrived, laughing it up. That was not uncommon. A woman with far too much drink on her brain for that early in the day turned to me - this poor, lonely writer with a red wine in one hand and a pen in the other - and made a highly lascivious suggestion. I did not need mastery of the language to understand her point. My adequate facility sufficed. They all laughed, toothed and toothless alike, as I turned crimson. I smiled at her, strangely flattered, and ordered another long glass of wine as I started into another chapter of my diaries. They went on to laugh and drink and I went on to keep writing that which, ironically, I have never been able to decipher thereafter. It is all written in uncrackable code.

Later I emerged out to the square and purchased some meat and vegetables from the stands in the open marketplace. We might call it farmer's market. And I returned to Árpád fejedelem in time to prepare a dinner for her, who had been at the office all day.

"How was your day? Did anything interesting happen?" she asked.

"Nah," I replied.

Mr. McAdams, your prose is pure poetry. This piece is like a blend of the best of Belloc and Robert Frost with a glazing of Roger Scruton. It magically transports the reader to your left elbow in that tavern of tradition, warmth, and, yes, love. Thank you sir.